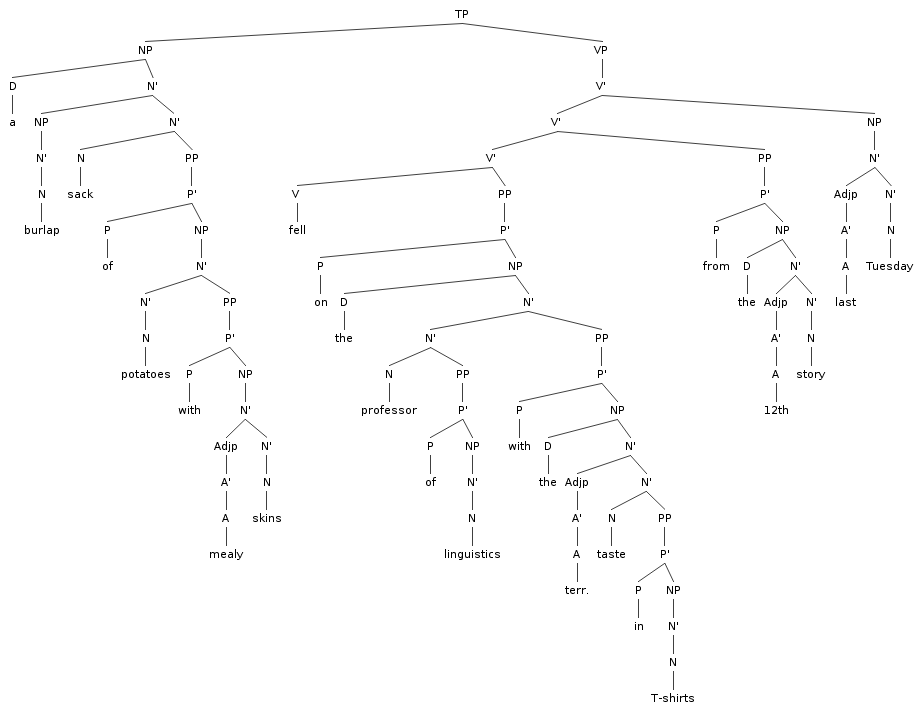

Chapter 6 Tree

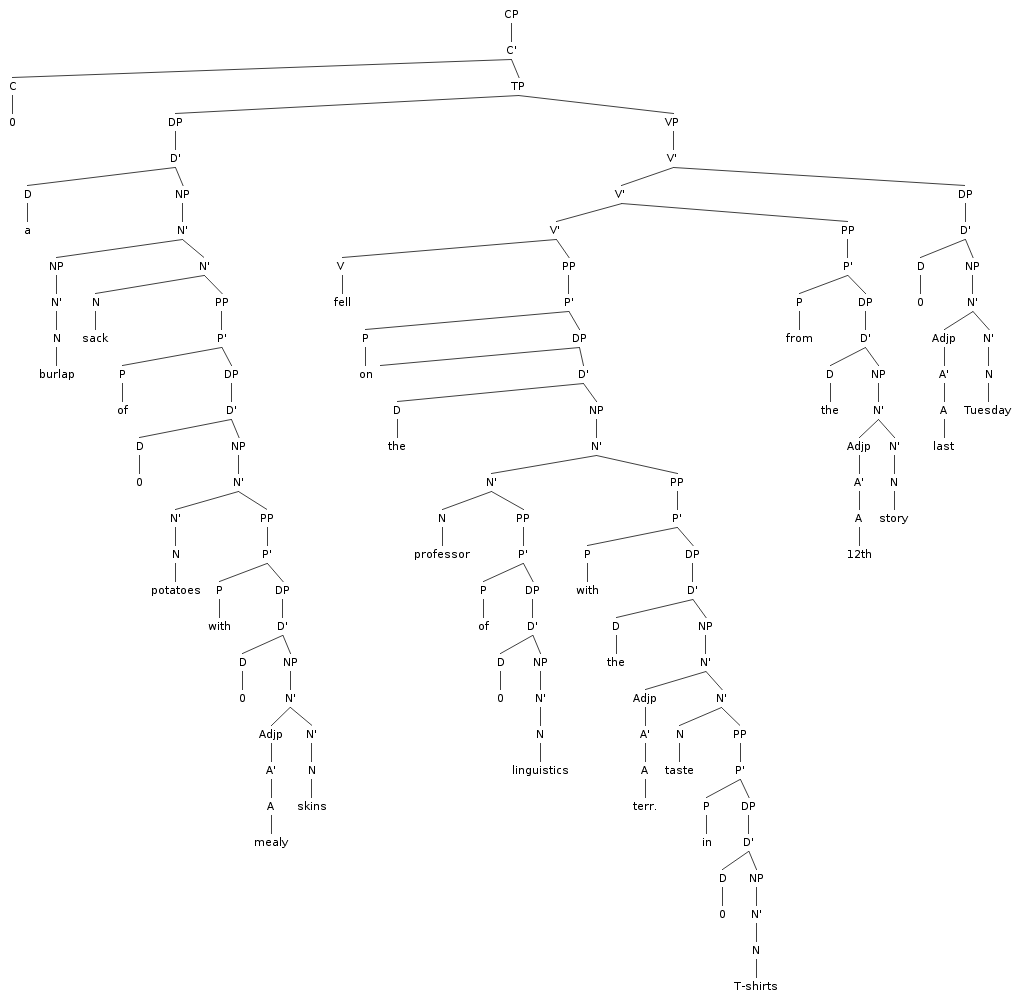

Chapter 7 Tree

Linguistics 522

Background Lecture

We assume the following PS-rules (phrase-structure rules):

The first thing these rules do is claim that there is a constituent

intermediate between an NP and lexical N. This will be a constituent

containing the head noun and its modifiers,

the italicized sequences in

the following NPs.

The other thing the 3 PS-rules do is distinguish between three kinds

of PP modifiers, Specifier, complements and adjuncts.

Here are some examples to motivate the distinction:

So far we only have rules for PP modifiers. Rules for other

types of modifiers will be given below.

There is a semantic intuition here which is not always

clear but can roughly described as follows. The adjunct

and the noun express two distinct properties of the individual

described. It can be paraphrased in two separate clauses:

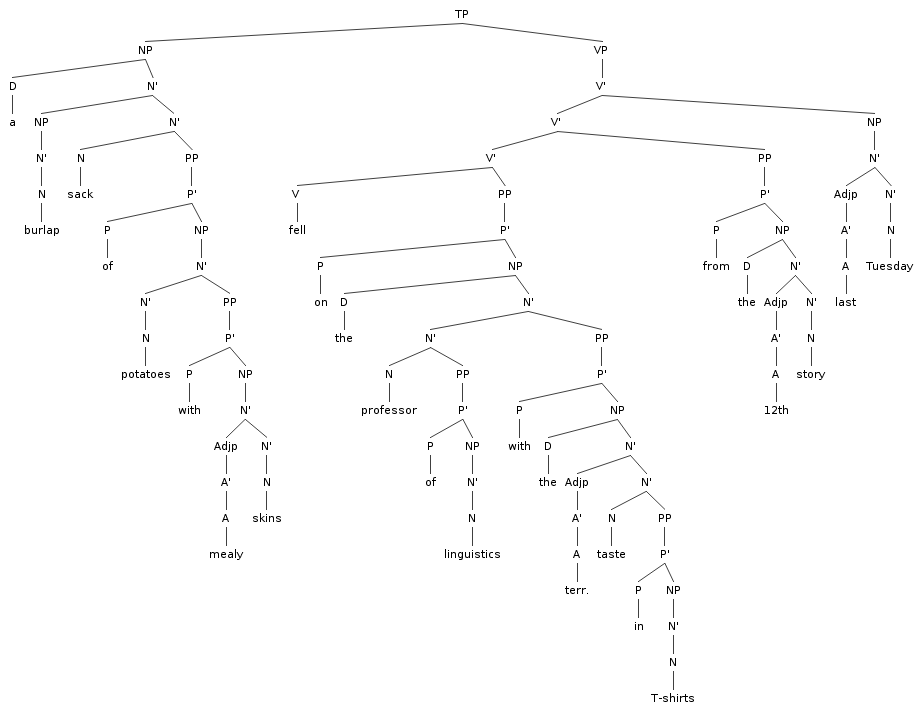

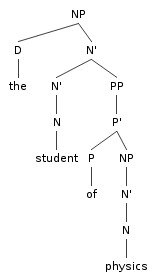

Figure 1

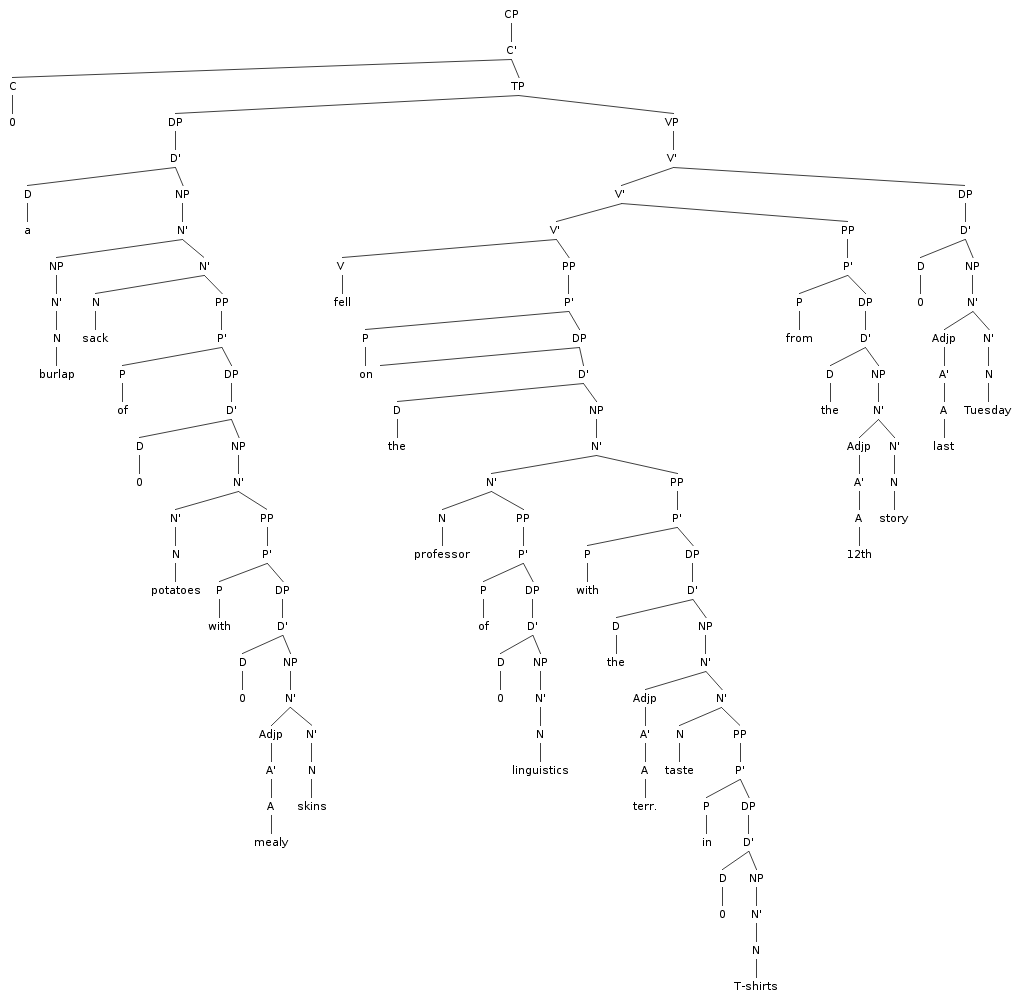

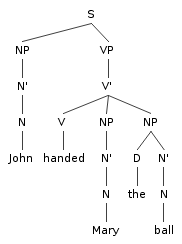

Figure 2

The complement and the noun function together to express one property,

which can be expressed in one clause, and not in two:

This semantic intuition is not very solid and the more you think

about it, the slipperier it gets. We are going to rely

on some syntactic tests to back the intuition up.

In determing whether a modifier is a complement or adjunct remember the following:

We introduce a set of tests for the complement/adjunct distinction. As a set of properties that all converge on making the same distinction they constitute an argument for it. Some of them are also simple predictions that follow directly from making this structural distinction.

|

Order of complements and adjuncts |

|

If you look closely at the complement and adjunct rules you will see that in any tree containing both a complement and an adjunct, the complement must always occur closer to the noun. This predicts the following facts:

|

|---|---|---|

|

Iterability of adjuncts |

|

The adjunct rule has the interesting property that it can be applied any number of times. It has an N' as both the mother and the daughter.

Note: Do not confuse this with the claim that there can only be one complement. This is wrong:

|

| one-anaphora | |

Note: The following test involves replacing an Nbar with one. It is only relevant when the head is a noun. One is an anaphoric element that seems to be able to take an entire N-bar as its antecedent.

We see the following contrast

|

| Do-so replacement | |

This works just like one- replacement only it is for use when the head is a V instead of an N. do so replace V's, just as one replaces N's,

|

| Coordination | |

We can coordinate adjuncts with adjuncts and complements with complements:

|

| Preposing | |

So far we've talked about predictions made by our structural assumptions. Now we just point to a syntactic fact that seems to be sensistive to our complement/adjunct distinction, without being able to say exactly why it's sensitive.

|

| Obligatoriness | |

In the theory developed in Chapter 8 it will become clear that ONLY complements can be obligatory. There will simply be no way to say that an adjunct is obligatory. Therefore it can be argued that all of the following modifiers are complements:

Notice the implication is valid in only ONE direction. If something is optional:

|

| Of-PP | |

Our textbook says that "all" PP complements are marked with of. As the list of examples under Obligatoriness above shows, this is wrong. Ignore this statement and never use it in an argument. On pain of excommunication. I'm not sure what he was thinking. Perhaps he meant: Almost all PPs marked with of are complements. This is a lot closer to true. But notice the almost, The ruling here: Dont use the identity of the preposition, of or otherwise, as an argument. It is an unreliable indicator at best. |

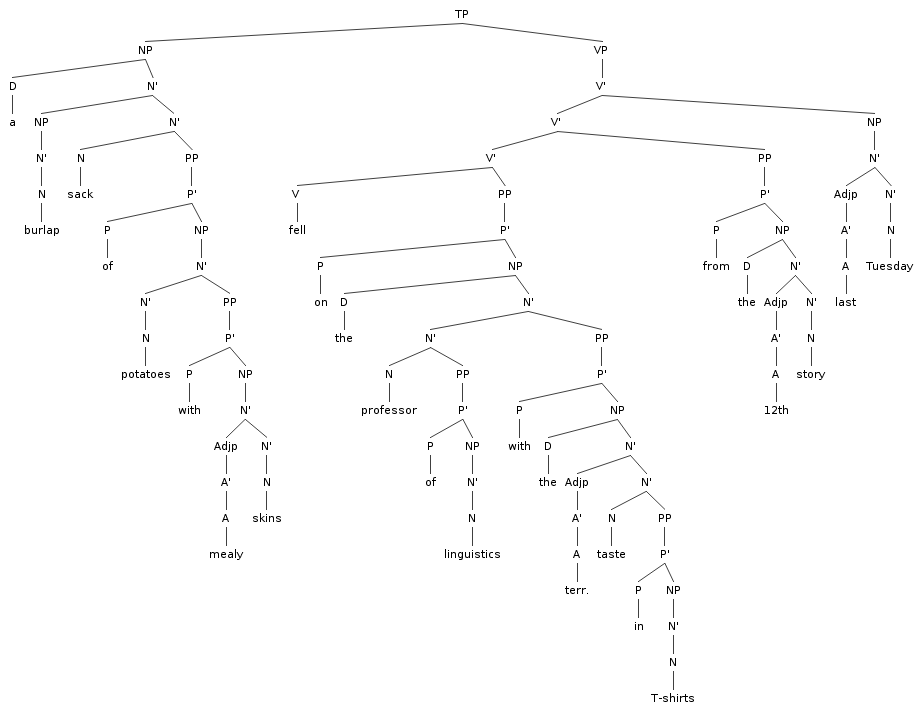

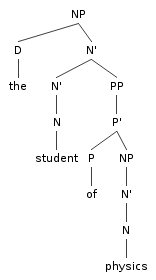

7 k from 194 (Ch. 6)

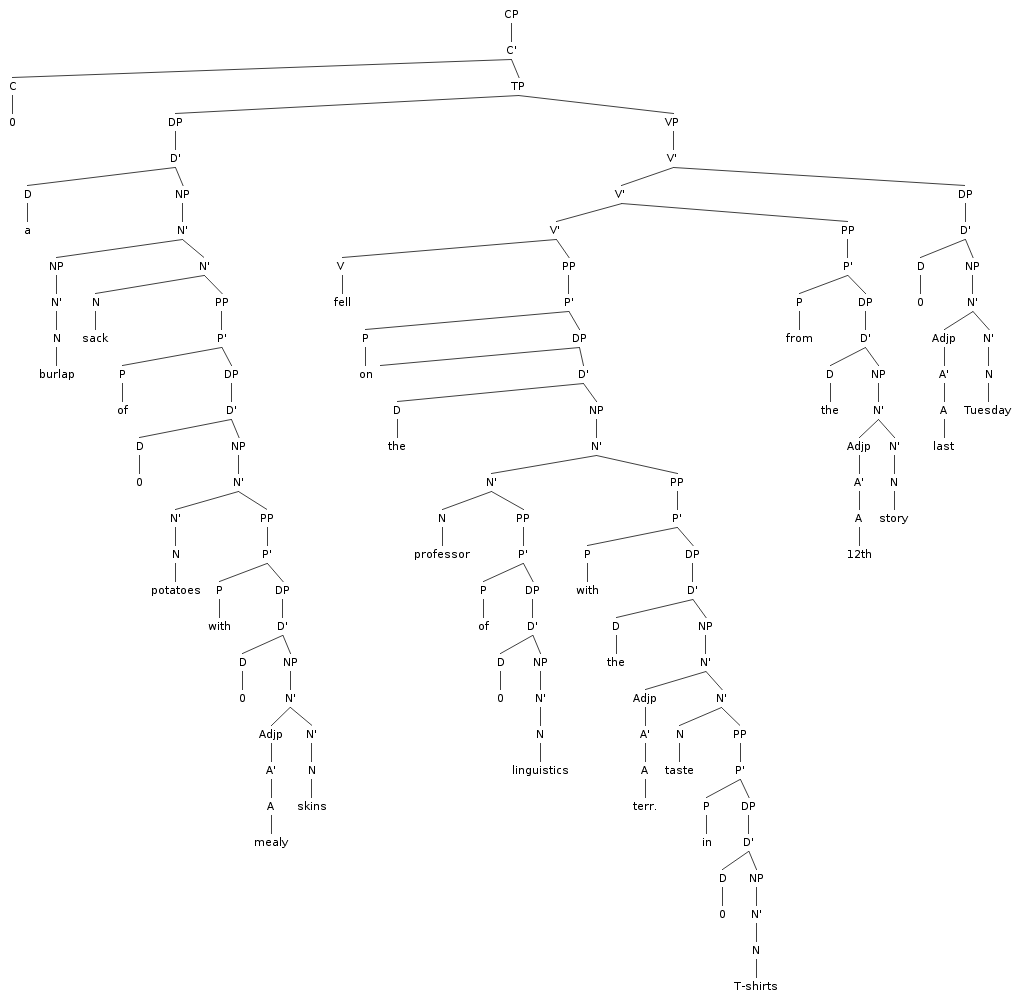

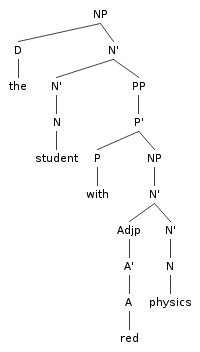

The same tree in the theory of Ch. 7

| prenominal np | |

We have the following order facts for some prenominal NP modifers.

Other complement/adjunct tests agree, all pointing toward complementhood of Physics in physics student and the adjuncthood of Oxford in Oxford student

|

|---|